Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs in Social Science Research

In social science research, the quest to establish causal relationships between variables often leads researchers to utilize experimental or quasi-experimental designs. These methodologies are pivotal in fields like economics, political science, and public health, where the impact of interventions must be accurately measured.

1. Introduction to Causal Inference

Causal inference aims to determine whether a change in one variable causes a change in another. In an ideal world, we would observe two identical units, apply a treatment to one, and compare the outcomes. However, in reality, we can only observe one outcome per unit at a time, necessitating methods that approximate this ideal.

The fundamental problem of causal inference is the counterfactual problem: we cannot observe the outcome of the treated unit had it not been treated. To address this, we use designs that control for confounding factors, ensuring that the treatment effect can be isolated.

2. Experimental Design

Experimental designs, particularly randomized controlled trials (RCTs), are considered the gold standard in causal inference. In an RCT, units are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups, ensuring that any differences in outcomes can be attributed to the treatment.

Let Yi(1) denote the potential outcome for unit i if treated, and Yi(0) denote the potential outcome if untreated. The treatment effect for unit i is:

τi = Yi(1) - Yi(0)

However, we can only observe one of these outcomes, so we estimate the average treatment effect (ATE):

ATE = E[Y(1)] - E[Y(0)]

In an RCT, randomization ensures that:

E[Y(1)|D=1] = E[Y(1)] and E[Y(0)|D=0] = E[Y(0)]

Thus, the difference in means between the treatment and control groups provides an unbiased estimate of the ATE.

3. Quasi-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental designs are used when randomization is not feasible. These designs seek to approximate experimental conditions by controlling for confounding variables through various techniques.

3.1 Common Quasi-Experimental Methods

1. Difference-in-Differences (DiD)

DiD compares the changes in outcomes over time between a treatment group and a control group. The key assumption is that, in the absence of treatment, the difference between the groups would remain constant over time.

Equation:

ΔDiD = (YT,post - YT,pre) - (YC,post - YC,pre)

Here, YT,post and YT,pre are the post- and pre-treatment outcomes for the treatment group, while YC,post and YC,pre are the corresponding outcomes for the control group.

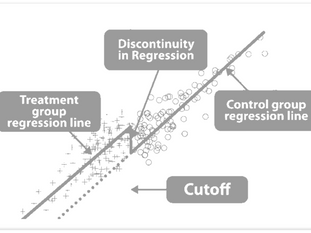

2. Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD)

RDD exploits a cutoff or threshold in an assignment variable to identify causal effects. Units just above and below the threshold are assumed to be comparable, with the discontinuity in outcomes attributed to the treatment.

Equation:

τ = lim_{x → c^+} E[Y|X=x] - lim_{x → c^-} E[Y|X=x]

Here, c is the cutoff point, and X is the assignment variable.

3. Instrumental Variables (IV)

IVs are used when there is concern about unobserved confounding. An instrument is a variable that affects the treatment but has no direct effect on the outcome, other than through the treatment.

Equation:

τ_{IV} = Cov(Y, Z) / Cov(D, Z)

Here, Z is the instrument, and D is the treatment variable.

4. Assumptions and Limitations

Each design relies on specific assumptions to identify causal effects. For example:

- RCTs assume perfect randomization and no interference between units.

- DiD assumes parallel trends, meaning the treatment and control groups would have followed the same trajectory in the absence of treatment.

- RDD requires that units cannot precisely manipulate the assignment variable.

- IV assumes the instrument is valid, meaning it is correlated with the treatment but not with the error term in the outcome equation.

Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased estimates, highlighting the importance of robustness checks and sensitivity analyses.

5. Conclusion

Experimental and quasi-experimental designs are powerful tools for causal inference, but they must be applied carefully. Understanding the underlying assumptions and potential pitfalls is crucial for producing reliable estimates. Researchers should complement these designs with robustness checks, such as placebo tests, falsification tests, and sensitivity analyses, to ensure their findings are credible.

As the field of causal inference continues to evolve, new methods and refinements to existing techniques will undoubtedly emerge, further enhancing our ability to draw valid conclusions from complex data.